Pope Leo XIV, a Chicago native and longtime missioner in Peru, is elected on the second day of the conclave, becoming the first American pope.

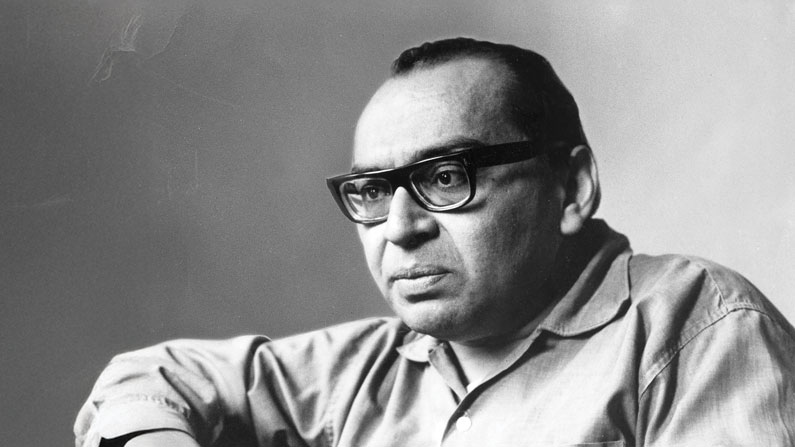

In our Spring 2025 issue, we visit the jungles of Guatemala, where Maryknoll priests have built a dozen chapels, and Hong Kong, where a school founded by the Maryknoll Sisters celebrates its centenary. Of note, too, in this issue is our tribute to the late Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, an Orbis Books author who is considered the father of liberation theology.

This Lenten season, join us in prayer with Maryknoll missioners who live and work in a spirit of hope.

Focused on Maryknoll missioners around the world working in solidarity among the poor and marginalized. Articles include issues of importance to people the missioners serve and to the Catholic Church.

Pope Leo XIV, a Chicago native and longtime missioner in Peru, is elected on the second day of the conclave, becoming the first American pope.

Pope Francis’ legacy of missionary discipleship will live on, writes the publisher of Maryknoll’s Orbis Books.

Maryknoll Father William Senger builds a parish in Guatemala by constructing chapels and forming lay leaders.

Maryknoll Convent School, a school founded by pioneering Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, celebrates its centenary the Maryknoll way.

Orbis Books Publisher Robert Ellsberg offers a tribute to Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, father of liberation theology.

Maryknoll Lay Missioners Joshua Sisolak and Marjorie Humphrey are commissioned to serve in Bolivia and East Africa.

Maryknoll Brother Joseph Bruener serves at a home for boys at risk of becoming street children in Cochabamba, Bolivia.

This second article of a four-part series presents the 14 Maryknoll bishops who attended the Second Vatican Council.

Jóse López, a Catholic leader who works in the Migrant Ministry for the Diocese of Stockton, California, brings hope to agricultural workers.

Latest news from mission sites and countries around the world.

A Maryknoll sister reflects on the Mass readings and Pope Francis’ encouragement to “smell like the sheep” in ministry.

Mass deportation could separate millions of U.S. children from undocumented parents and push thousands into foster care, a study warns.

As a final act of compassion, Pope Francis donated his popemobile to be converted into a mobile health for vulnerable children in Gaza.

Pope Francis was remembered as a tireless and faithful shepherd during the last Mass of a nine-day period of mourning at the Vatican.

Maryknoll Father Thomas Tiscornia reflects on saying “yes” to Jesus in the context of his mission in Sudan and the Sunday Mass readings

Families came from all over the world for the Jubilee of People with Disabilities Mass at the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome.

During his 12 years of papacy, Pope Francis appointed several women to positions of importance, opening roles of leadership in the Church.

Fifty years on, the Church walks with Cambodians in rebuilding their country and healing their painfull past.

The late pontiff put the poor ‘at the center’ of his papacy, says the prefect for the Dicastery of the Service of Charity.

Advocacy for migrants and refugees was a key cause for Pope Francis, who lamented the ‘globalization of indifference’ to their plight.

Pope Francis brought the voice and vision of Latin America to the heart of the Church, defending...

Care for creation was a signature of Pope Francis’ papacy, building on his predecessors’ examples and imitating Saint Francis of Assisi.

Pope Francis died early in the morning today, Easter Monday, April 21, 2025, at the age of 88. He served as pontiff for 12 years.

“Seeing is believing” is a phrase applied by Maryknoll Sister Teresa Dagdag, who serves in the Philippines, to the Easter Sunday readings.

Maryknoll Father Joseph Veneroso explores the theme of light in Scripture and in the liturgies of Holy Week, especially the Easter Vigil.

Fung-Bing Ho is a long-time Maryknoll partner in mission, now serving in a parish where Maryknoll Father Daniel Kim ministers in Hong Kong.

Vignettes from the lands of mission, told by Maryknoll missioners and volunteers. These popular little stories are sometimes funny, often moving and generally inspiring encounters with people on the margins.

Missioners share vignettes of life drawn from their Maryknoll ministries in Bolivia, Guatemala, Tanzania and Brazil.

Pope Francis has called on world leaders to consider debt cancellation for poor countries as a way to honor the Jubilee Year.

Readers respond via email, letter or message to our stories published online, circulated in print and shared weekly by ezine.

Notifications