Orbis Book Spotlight

[googlefont font=“Cormorant Infant” fontsize=”20″]preview by Robert Ellsberg[/googlefont]

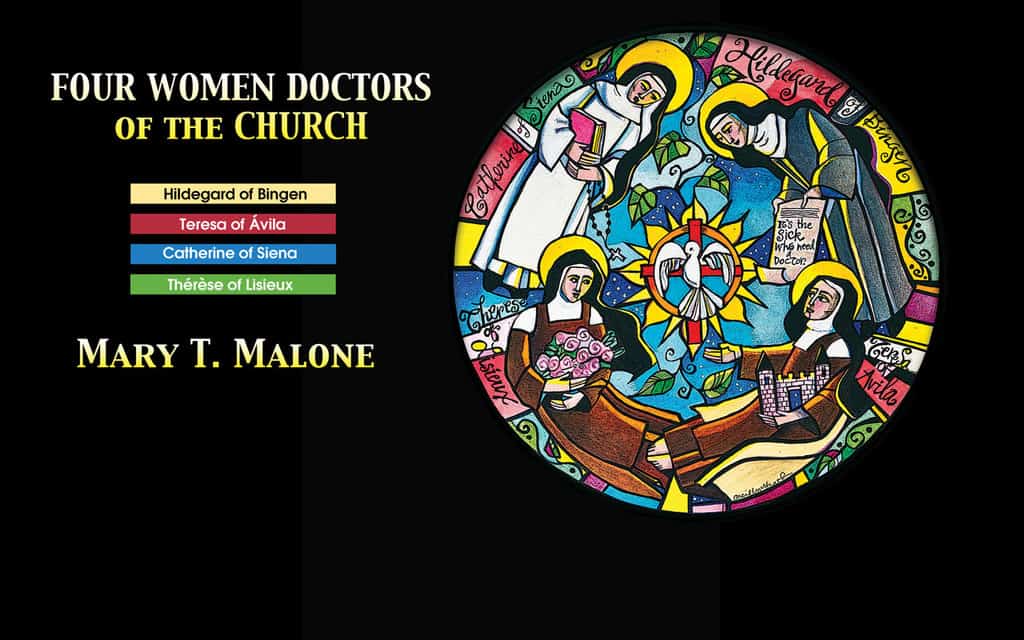

Among the 36 official “Doctors of the Church” are four women—all named in the past 50 years, though the earliest of them lived nearly 1,000 years ago. In this new Orbis book, theologian Mary T. Malone explores the stories of these visionaries and captures their message for the contemporary Church. These women doctors of the Church are:

• St. Hildegard of Bingen, a Benedictine abbess who lived in Germany in the 12th century. She was a prophet and preacher, musician and composer, poet and artist, whose writings included extensive studies of the medicinal properties of plants. She devised a complex theology from her mystical visions, in which she saw human beings and the cosmos as “living sparks” of God’s love. Her holistic vision, rediscovered in the 20th century, had an enormous influence on contemporary spirituality.

• St. Catherine of Siena, who lived in the 14th century, was a Third Order Dominican. After experiencing what she called a mystical marriage with Christ, she undertook a mission of caring for the sick. Eventually she felt called to reform and heal the Church, challenging the pope to leave Avignon and return to Rome. She also recorded several volumes of her mystical dialogues with Christ.

• St. Teresa of Avila, who lived in 16th-century Spain, was an indomitable reformer of the Carmelite Order and the author of several classics of mystical theology. Withstanding scrutiny from the Inquisition, she became one of the most influential women of her time.

• St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who died in 1897 in a Carmelite convent in Normandy, achieved extraordinary renown through the posthumous publication of her autobiography. In that short book she laid out the principles of her “science of sanctity,” which she called “the Little Way.” By responding with love to one’s daily encounters, she taught, one could transform any situation into an arena of holiness.

As Malone shows, these extraordinary women demonstrated independence and courage in pursuing their own religious vision, even when this meant challenging restrictive roles for women in the Church and society. Malone writes, “It is obvious that they are always conscious of their restricted role in the Church. Catherine complains about the limitations of being a woman. Teresa of Avila is always conscious of the Spanish Inquisition constantly monitoring her audacity to teach as a woman. Even the mighty Hildegard comes up against ecclesiastical intransigence during her long life, leading eventually to the excommunication of herself and her whole monastery, shortly before death.”

Pope Paul VI was the innovator in recognizing the teaching authority of these women. In 1970 he declared Catherine of Siena a Doctor of the Church, representing all laywomen, and Teresa of Avila a Doctor of the Church, representing all religious women. St. Thérèse followed in 1997, and Hildegard in 2012. They have a universal meaning that speaks to our own time. As Malone writes, “these women took the initiative, based on their relationship with God, to launch themselves into the life of the Church. … All were called and loved by God. And it was love that was at the center of their lives. … Above all, each learned her full humanity from Jesus’ humanity. Hopefully the teaching of these four women will become as familiar and influential in our lives as the teachings of the male doctors. The message of these women is more than timely.”

To find more information on the book, or to purchase, please visit OrbisBooks.com