On the site of the killing of African-American George Floyd, a white, suburban Minneapolis man vows to combat racism.

Late in April 1992, as I made my way home after dark in a West Philadelphia neighborhood, I was set upon by a small group of youths carrying bats and boards. Hours earlier, a largely white jury had acquitted Los Angeles police officers of the brutal beating, captured on video, of Rodney King, an African-American man detained after a high-speed car chase. Los Angeles exploded into riot and arson. Across the country, Philadelphia hunkered down in fear. Even the homeless men with whom I worked as a Mercy Volunteer Corps volunteer were unusually subdued.

As I walked the final blocks home that evening, the group of youths caught sight of me. They laughed and jostled each other as they crossed the street to trap me. I had no time to think or even experience much fear before one of them struck me over the head and shoulders with a board. As I fell to the pavement, he leaned over and said, “Tonight, we’re white and you get to be black.” And, with that, it was over. He leaned back up and, together with his friends, ambled away in laughter, leaving me sprawled alone on the sidewalk.

As I lay in shock, I soon felt an arm reach down and hook itself under mine. It belonged to one of the youths. He didn’t say anything. He didn’t even look at me. He just lifted me up and, when I was steady, let go and walked away just as silently to rejoin his friends.

After arriving home, I leaned back in safety on the closed door and started laughing and sobbing in the same halting breaths—laughing from relief that I returned intact and largely unhurt, and sobbing for reasons I still don’t quite understand to this day.

Mural calls all, including a little girl, to remember and pray for George Floyd and all victims of police brutality. (Greg Darr/U.S.)

Mural calls all, including a little girl, to remember and pray for George Floyd and all victims of police brutality. (Greg Darr/U.S.)

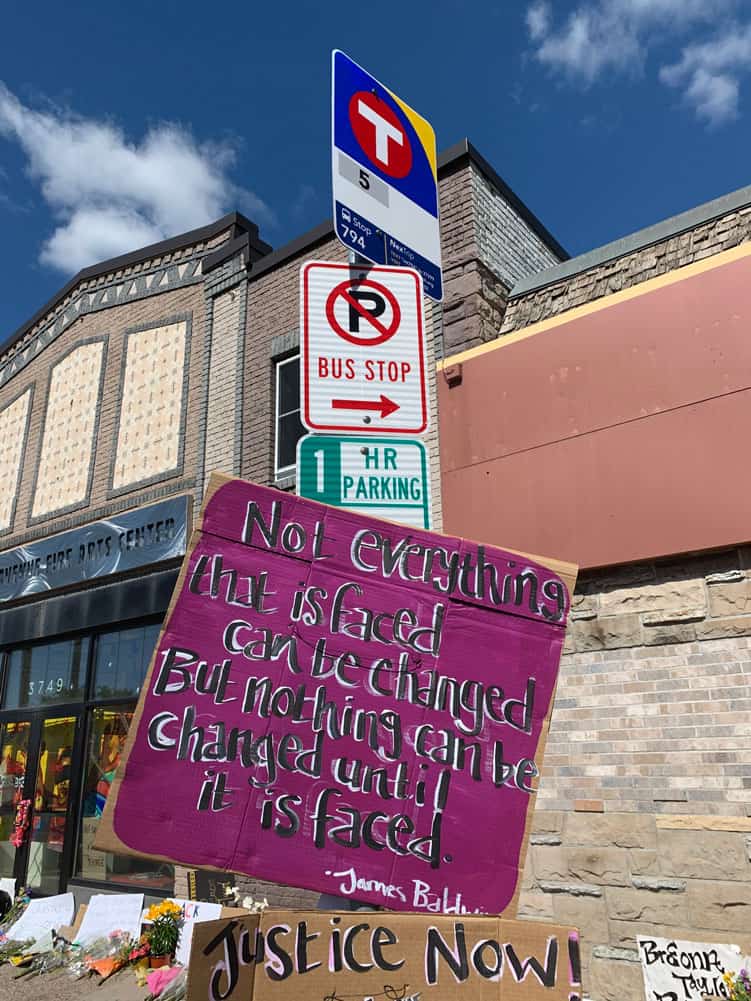

This memory returned to me on the corner of 38th and Chicago a few days after George Floyd, an African-American man, had been tortuously killed there by Minneapolis police officers. My family and I had come to lay flowers at an improvised but rapidly growing memorial for him and other victims of police brutality. A few blocks to the north, a commercial neighborhood that I know well, lay in smoldering ruins. Later that night, the riots and fires would return.

At 38th and Chicago, however, my family and I experienced a surprising sense of peace. People of all colors and all walks of life—many of them together as families—came to share their grief, their stories, their fears and their hopes. In a frightened and besieged city, this intersection emerged as a singular place of personal and spiritual refuge.

It wasn’t long before my wife and two high-school-age daughters were enlisted by strangers to help paint banners, signage alerting arriving protesters or police of what we and many others already sensed: this was sacred space. In the meantime, organizers broke open boxes and distributed masks to those in need of COVID-19 protection. People did their best to maintain social distancing but, with that crowd size, it was nearly impossible.

As I listened to speaker after speaker relate experiences of police brutality and racism, protests and prayers intermingled to the point where they were no longer distinct. “How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever … Having sorrow in my heart all the day?” (Psalm 13) Psalmists and prophets would be “homies” in this crowd, their inspiration, if not their words, rendered now in hip-hop cadence.

Darr’s daughters, Louisa and Rita, and a friend make banners before a vigil in honor of George Floyd, showing the place of the makeshift memorial is a sacred space. (Photos by Greg Darr/U.S.)

It wasn’t hard for me, a white man standing there, to recognize that there’s not much systemically stacked against me. Even as a Maryknoll missionary in East Africa, I lived and worked in a bubble of racial privilege conferred upon me at birth. I can’t change my skin color. But I can broaden my awareness and do my part, in solidarity with others, to lift unjust burdens that people of color carry on my behalf. It won’t be easy, certainly for me. It’s going to take patience, perseverance and, most of all, grace.

As I watched the bouquets, signs and written condolences pile higher in memory of George Floyd, I felt that grace move my heart. It was then I recalled that long-ago Philadelphia night and remembered, with gratitude, the youths who ambushed me and then helped me to my feet again. I gave thanks for the lessons they taught me. In a moment of violence and then compassion, they mocked my privileged innocence to a point where I could see it. They lifted me out of my lethargy and indifference in matters of race. And, they helped me to understand how racism stunts the emotional, mental, physical and spiritual health of everyone touched by it, including those privileged enough to believe it’s not their problem. Most of all, considering the violence and poverty these youths faced daily, I experienced an extraordinary degree of mercy from them. I walked home a few bruises wiser and my wallet still in my pocket. These young men, on the other hand, walked from the scene down a far harder road. I wondered where it had taken them. Or, for someone like George Floyd, how far.

As I asked myself these questions, I watched a young man walk solemnly up to a mural painted in memory of George Floyd and other victims of police violence. He knelt, made the Sign of the Cross and prayed for a few moments. He again made the Sign of the Cross as he stood up and walked quietly away. Nearby, a little girl apparently took note of the young man’s prayer. She stepped from her caregivers, returned to the mural where I had seen her wandering earlier, and knelt alone in her own sacred way of stillness.

Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Jewish scholar who, in 1965, participated in the Selma march with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., observed, “Prayer is meaningless unless it is subversive, unless it seeks to overthrow and to ruin the pyramids of callousness, hatred, opportunism, falsehoods.”

Prayer brings us to our knees. But, in matters of racism, justice and peace, it also hooks its arm under ours, lifts us up and sets us walking together on that hard uncertain road ahead. I stepped anew from the corner of 38th and Chicago, in memory of George Floyd and countless others, resolved to continue, with my brothers and sisters of color, on our way to the Promised Land.

Featured Image: A little girl prays at a mural in memory of George Floyd and other victims of police violence. (Greg Darr/U.S.)

Maryknoll employee and his family in Minneapolis join others in mourning the death of George Floyd and calling for an end to police brutality and racism throughout the United States. (Photos by Greg Darr/U.S.)

![]()