A former altar boy from Korea remembers Maryknoll’s service in his homeland.

On celebrating the 100th anniversary of Maryknoll’s arrival to Korea, I recall the missions and sacrifices of Maryknoll priests, brothers and sisters to whom I am indebted immensely. Among those who raised me spiritually, Maryknoll missioners have significantly shaped who I am.

A century ago, the Holy See commissioned the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America to minister to the Pyongyang area in what is today North Korea. Father Patrick J. Byrne arrived on May 10, 1923 and was named prefect apostolic when the Pyongyang Diocese was established four years later. (The Maryknoll Society would also be entrusted with the apostolic vicariates that became the Cheongju Diocese and the Incheon Diocese.)

Six Maryknoll sisters arrived in 1924, and each of the ensuing years saw additional missioners sent to Korea. Through the sisters’ efforts, under Monsignor John Morris, the Sisters of Our Lady of Perpetual Help was established — the first local Korean congregation. Maryknoll Sister Agneta Chang, who had undergone novitiate training at the motherhouse in New York, was assigned to oversee the novices’ spiritual formation.

Monsignor Patrick J. Byrne, who opened Maryknoll’s Korea mission a century ago, was consecrated bishop in Seoul in 1949. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

During World War II, non-Korean missioners were expelled and evacuated. After much petitioning, Maryknoll was allowed to return after the war to the newly partitioned Korea. Monsignor Byrne was assigned to Seoul, where he was consecrated bishop.

However, the Communists of North Korea attacked and took over the South in 1950.

Detained and executed, Sister Chang became a modern-day martyr, along with countless others. I grew up hearing their stories. They reminded me of the more than 20,000 Korean martyrs, including 103 saints and 123 blesseds, who had chosen God instead of apostasy, enduring brutal tortures in the Yi dynasty.

The ordeal of Bishop Byrne and his assistant Father William R. Booth made me cry. As the Communists approached, Bishop Byrne decided not to flee, saying, “As long as Korean Catholics and clergy stay in Seoul, I have to be with them.” The missioners were captured and forced to join the “Death March” to North Korea through the unbearably cold winter.

Bishop Byrne died on Nov. 25, 1950, from the hardships he endured. His last words included his saying, “It has always been my wish to lay down my life for the sake of my faith, and a good God has given me this grace.”

The Korean War, from 1950 to 1953, devastated Koreans physically and mentally. Maryknoll members chose to care for war-torn South Koreans, giving up the wealth and honor they could have enjoyed in the United States. They built churches, schools, orphanages and hospitals — demonstrating what the love of God truly means.

Maryknoll Sisters Sylvester Collins and Agneta Chang (right) are shown in 1939 with Our Lady of Perpetual Help novices. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

Medical services were urgently needed during and after the war, and Maryknoll established six clinics and joined other hospitals providing services throughout the country. (Earlier, Sister Mercy Hirschboeck, a doctor, had founded Korea’s first Catholic medical facility in 1933.) Physicians, including Father Gerald J. Farrell and Sister Anna Boland, and nurses, including Sisters Rose Guercio, Augusta Hock and Jean Maloney, saved thousands of lives.

Sister Boland visited rural areas on foot to treat patients. She became an expert in snake venom detoxification. Sister Guercio established an affordable health insurance system. Sister Maloney — who seven decades later still lives in Korea — would go on to co-found Magdalena House for exploited women.

When I was young, I didn’t understand why the Maryknoll missioners voluntarily went through such hardship, living in exemplary frugality and service. But now, having lived a happy and blessed life for 80 years, I know how noble was the love they practiced, and how immensely they influenced my life. They seeded hope in the hearts of distressed Koreans for a better future in this world — and in the world that follows.

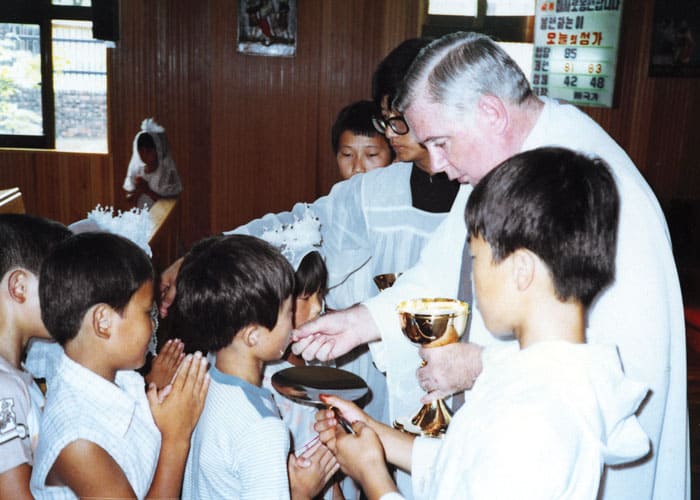

Father William John McNaughton arrived in 1955 at Cheongju parish, where I served as an altar boy. Often, I saw the priest kneel before the altar to pray. That sacred image is firmly etched in my heart. Thus began my bond with Maryknoll religious.

Maryknoll Sister Jean Maloney (in habit), a nurse, has lived for 70 years in Korea, where she has served in various ministries for the sick, workers and exploited women. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

Korean society has been autocratic and hierarchical. Since Korean Catholics were familiar with strict and authoritative priests, parishioners were confused by the Maryknoll members who approached them with friendly smiles.

As a pastor, Father McNaughton tried to honor and practice the Korean customs of hospitality. When parishioners visited, he greeted them by serving watermelon or homemade cookies. That practice won the parishioners’ hearts.

Even after he was consecrated Bishop of Incheon in 1961 — becoming Korea’s fourth Maryknoll bishop — Bishop McNaughton maintained a frugal lifestyle. His nickname was “the Subway Bishop” since he used the subways to visit his parishes. Approached once by a beggar, a story tells, he gave the man his own bishop’s robe since he had nothing else to offer. This anecdote teaches Christians what God’s love is.

Father Gerard Hammond, first assigned to Korea in 1960 — and still serving — has visited the communist North more than 60 times to help tuberculosis patients. He says he prays daily “that my heart will be like a Korean’s.”

One of the first Maryknoll missioners sent to Korea, Sister Gabriella Mulherin in 1960 helped establish a credit union movement. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

The late Father Raymond Francis Sullivan, a musician and singer who pioneered evangelization through the media, once reflected, “The time I lived in Korea … I received all the blessings I could have received.”

Generations of Koreans were also blessed, myself among them. Fathers Roy Petipren and John J. Kelly Walsh taught me English when I was in middle school. I remember not correctly answering Father Roy’s question of how many syllables are in the word “difficult.” But I couldn’t have completed my master’s and doctorate degrees at distinguished U.S. universities, nor accomplished a successful career as a professor, if not for their dedicated teaching.

Maryknoll continues its mission in Korea, while having achieved the goal of transitioning parishes, dioceses, schools and medical facilities to the auspices of the local church. When he retired, Father Robert M. Lilly, a Maryknoll priest who served in the Cheongju Diocese, said, “There was not one Korean priest when I arrived. I now gladly depart the diocese entrusting it to 120 Korean priests.”

Maryknoll Father Gerard Hammond, first assigned to Korea in 1960, still serves there. The missioner carries out trips to the North to help tuberculosis patients. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

“If I speak in human and angelic tongues but do not have love, I am a resounding gong or a clashing cymbal,” wrote Saint Paul. “Faith, hope and love remain … but the greatest of these is love.” (1 Corinthians 13: 1, 13)

Maryknoll members have manifested love in action in Korea. They planted the seed of love that originated at Mary’s Knoll, and which for a century has been growing and blossoming in Korean hearts. I am a recipient of that seed.

Featured image: Bishop William J. McNaughton was pastor where the author served as an altar boy. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

![]()