A young Catholic artist, Jacqueline Romo, draws inspiration from her faith and the lived experience of the migrant journey.

For Jaqueline Romo, an artist, teacher and immigrant, the migration experience that she, her family and friends and many others have endured is aptly reflected in the Stations of the Cross.

Migration, with its sufferings and sacrifices, is a Way of the Cross for many of us Latinos in the United States and elsewhere. That is why we identify so strongly with Good Friday and the Passion of Christ. When blended with art, culture and mysticism in the Catholic imagination, migration experiences can become fertile ground for theological reflection by Latinos who migrate to the United States, as in Romo’s case.

“I decided to make art in a Latino way, in other words, through the eyes of a Latina migrant,” she says.

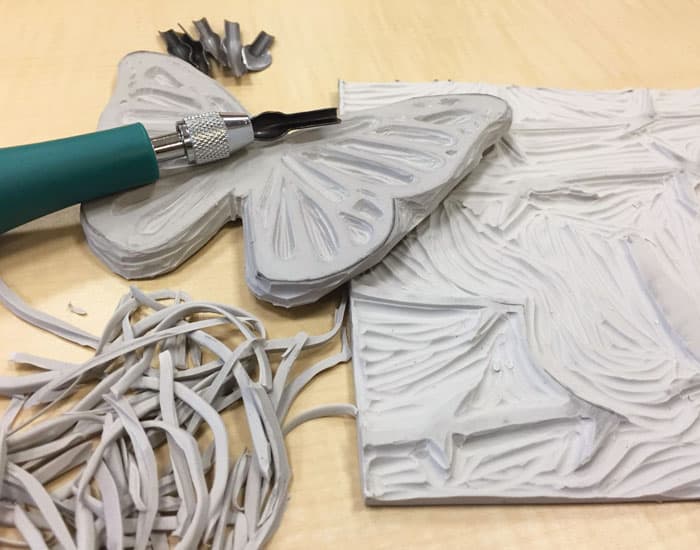

Her work, “The Passion of the Monarca Migrante,” is composed of 15 prints made from carved linoleum blocks, called linocuts, to represent the Way of the Cross. In Romo’s rendering, Jesus is simultaneously represented as a monarch butterfly and the body of a migrant pushed to the margins of society.

Romo, 26, was born in Los Altos, Jalisco, Mexico, and migrated to the United States with her parents when she was just 2 years old. She and her two siblings had a difficult childhood, and she was traumatized when her father was deported to Mexico. “My mom had to raise the three of us, and she was the one who had to work to support us,” Romo recalls. Yet, from the time Romo was young, her mother instilled the Catholic faith in her children, which helped Romo cope with the loss. “Going to church helped me move beyond my father being deported,” she says.

Closeup of tools and linoleum blocks used to create Jaqueline Romo’s “The Passion of the Monarca Migrante,” depicting the migrant journey through the Stations of the Cross. (Courtesy of Jaqueline Romo/U.S.)

Romo’s family lived in the south side of Chicago, in the predominantly Mexican La Villita-Pilsen area, known for its picturesque murals. “I grew up among all that,” Romo says. She also recalls, “My father is the artist of the family, and very creative.”

After finishing two years of community college, Romo, who is a recipient of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, received a scholarship to study for a bachelor’s in graphic design at Dominican University in the suburban Chicago area. While she was still completing her bachelor’s degree, Romo was offered the opportunity to study for a master’s degree in theology at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago.

For her senior art thesis project at Dominican, she drew upon her theological studies. Romo realized that the date she was to present her thesis project fell close to Palm Sunday, when the Gospel reading is the Passion of Christ.

“I know that passage well, and I know the Stations of the Cross,” she says. “I decided to focus on the Mexican experience of crossing the border, not because Mexicans are the only ones — they are not — but because that was the way I would portray myself in this work, reflecting on what the Passion of Christ means to a Latino in the United States and portraying the untold stories of people who cross a desert, a river, not knowing if they will make it.”

A few prints are assembled on Romo’s living room floor in Chicago as the artist created her senior thesis project for a bachelor’s degree in graphic design at Dominican Univesrity. (Courtesy of Jaqueline Romo/U.S.)

She recalled that the monarch butterfly has been used as a symbol of resilience by immigrants in the States, given the long journey it undertakes. It flies north to the United States and Canada each year and then travels back again to Mexico.

“The Passion of the Monarca Migrante” was a collective work, says Romo, who prefers to keep the title bilingual, reflecting the mixing of English and Spanish, or Spanglish, that Latino migrants often use. “I didn’t do it alone,” she says. “I consulted with classmates, friends and people around me. I also recalled the migration stories told to me by my aunts, uncles and cousins, stories about how they went through the desert and crossed the border.”

She continues, “Many of the stories were similar, but none were the same. Still, I could see similarities in the stories of suffering, sacrifice, faith and hope.”

Romo notes that the fourth station reflects the strong Catholic faith of migrants. “When the bodies of migrants are found in the desert, often they are carrying holy cards of the Virgin of Guadalupe or Saint Toribio, or a rosary or scapular,” she says.

While she likes all the images in the series she made, Romo feels especially drawn to the eighth station, when Jesus consoles the Women of Jerusalem. “It is a moment in which Jesus is suffering and when he should be the one being consoled,” she says. “Yet, it’s the reverse — he consoles the people who are suffering. That’s why I portray Jesus as a monarch embracing the women who are on a path. They aren’t alone; they are with Jesus. In spite of all the suffering, Jesus doesn’t abandon them.”

Jaqueline Romo (left) and her mother, Gila Estrada, are shown at the opening of the Senior Art Exhibition in the O’Connor Art Gallery at Dominican University in Chicago in 2019. (Courtesy of Jaqueline Romo/U.S.)

Another station that particularly impacts her is the 12th, when Jesus dies on the Cross. Originally, Romo did not want to use the color orange on that station and intended to leave it black as a sign of mourning. But, she says, “Accidentally, I used a little bit of orange. I thought, that was as it should be since the orange color should return through the light of Christ at the Resurrection.”

Romo says she asked her classmates about what Jesus’ resurrection might mean to Latinos. “For us the American dream is to graduate, or that our children graduate,” she says. “Reaching a bachelor’s or a master’s degree in the United States is the highest achievement for us and our parents.” With that in mind, she says the 15th station, the Resurrection, is the station with which she most identifies.

“Because I could make it to graduate from college after so much sacrifice by both me and my parents — especially my mom, coming to a new country, without knowing anything and having to navigate everything by herself,” she says. “For me it was an accomplishment, giving my mom the opportunity to see me graduate and finally say, ‘Here, I am, at this station, the Resurrection.’”

Currently, Romo works at Cristo Rey High School in Chicago, ministering to youth and sharing the integration of art, theology and her life experience as a woman migrant.

Featured image: Jaqueline Romo’s artwork is composed of 15 linocut prints paralleling the Stations of the Cross and using the symbolism of the monarch butterfly. (Courtesy of Jaqueline Romo/U.S.)

![]()