Maryknoll lay missioner fights for safety

of migrant women in ICE custody in El Paso

Maryknoll Lay Missioner Heidi Cerneka is sounding the alarm about the life-threatening consequences of immigration policies at the U.S.-Mexico border during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cerneka, a pro bono attorney for detained migrants, is representing the immigration cases of two women who, along with four other detained women, successfully filed a federal lawsuit against Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). All six of the women presented high risk for infection, and they argued that the agency was making them vulnerable by not following COVID-19 safety guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for detention centers.

Rosa, one of Cerneka’s two clients, is a former law student from Guatemala. She was seeking asylum after fleeing death threats because of her evangelical Christian religion and indigenous ethnicity.

While waiting for her asylum case to be heard, Rosa was held in detention in El Paso, Texas, where she developed multiple health issues. On April 7, she filed a request for release from detention. Her health issues put her at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19, which should have been flagged by ICE, Cerneka said. Rosa was denied.

When Rosa complained of symptoms and asked for medical attention, she was told to “drink water.”

On April 20, Rosa—who had been separated for observation—began coughing up blood and demanded to be tested for coronavirus. She tested positive. “Rosa told me, ‘When I left my country, I had no health problems. Now I have COVID-19 and many other symptoms, and I am only 25,’ ” recalled Cerneka, who works at Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center in El Paso.

Heidi Cerneka, a pro bono attorney for detained migrants through Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, talks to clients in El Paso, Texas. (Meinrad Scherer-Emunds/U.S.)

Cerneka’s other client who was part of the lawsuit is Mariela, a 60-year-old Colombian woman with a thyroid disorder and other health issues. “She called me crying because she was depressed and scared. She said, ‘I don’t want to die here,’ and I told her, ‘You are NOT going to die in detention,’ ” said Cerneka.

She explained that Mariela, who has a U.S. visa, has visited her fiancé in El Paso since 2012, never violating her visa requirements. However, when she and her fiancé were returning to El Paso from a day visit to Mexico early this year, Border Patrol stopped her and accused her of working in the United States.

She was detained for 10 weeks to await deportation. “In no way is she a threat to society,” Cerneka said. “She is not even at risk of trying to stay here undocumented; she owns businesses in Colombia. She was, however, at risk of catching COVID-19 and dying in detention.”

Rosa, Mariela and the other women who sued ICE had all been held at El Paso Processing Center, where, as of April 30, nine cases of COVID-19 were confirmed. The six women had been in contact with other detainees who had contracted COVID-19.

“People who have never committed a crime in their lives, who came to the United States to ask for protection and asylum, are now being detained in tinderboxes just waiting for a match,” Cerneka said. Prisons and detention centers—like shelters, hospitals and other places where people live in close quarters—are “known to be places where infections spread at lightning speed,” she explained.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s El Paso Processing Center. (Courtesy of Bob Moore, El Paso Matters/U.S.)

According to the lawsuit, El Paso detainees were sleeping in bunk beds in dormitory-style rooms with dozens of others. The lawsuit alleged that physical distancing was not being observed, as detainees were eating and socializing in close contact and were prohibited from wearing face coverings. And, the lawsuit said, before April 17, ICE rarely cleaned the barracks and common areas.

Recently, prisons and jails in the United States and other countries have been trying to reduce the coronavirus threat for their incarcerated populations by releasing those who have not committed violent crimes or are still waiting for trial, and whose health could be at risk.

But, Cerneka said, in El Paso, immigration detention for people who are not dangerous has remained mostly unchanged.

The more than 300 detainees held at the El Paso Processing Center are part of 28,000 people detained by the agency nationwide. As of May 18, ICE reported 1,073 COVID-19 infections among its detainees and 44 cases among its staff. Overall, only about 7.8 percent of the 28,000 immigrants detained by ICE have been tested, reports show. Of those, about 50 percent have been positive.

ICE and the lawyers for the women settled the lawsuit just minutes before a hearing at the end of April. ICE agreed to release the women from its custody, and the women, who were released on April 29, agreed to comply with the ICE “alternatives to detention” program, which sometimes includes wearing an ankle monitor. Upon release, the women were tested for COVID-19, quarantined themselves and were able to access medical care and to reunite with their loved ones safely.

“Today we celebrate their release, but they should never have been detained,” said Cerneka, adding that the lawsuit is believed to be the first time ICE has settled such a suit.

“It will take years to recover their health, their sense of trust and safety after the physical and emotional trauma and damage caused by unnecessary custody. Justice delayed is justice denied. Today’s release of Mariela and Rosa is extremely delayed justice for them.”

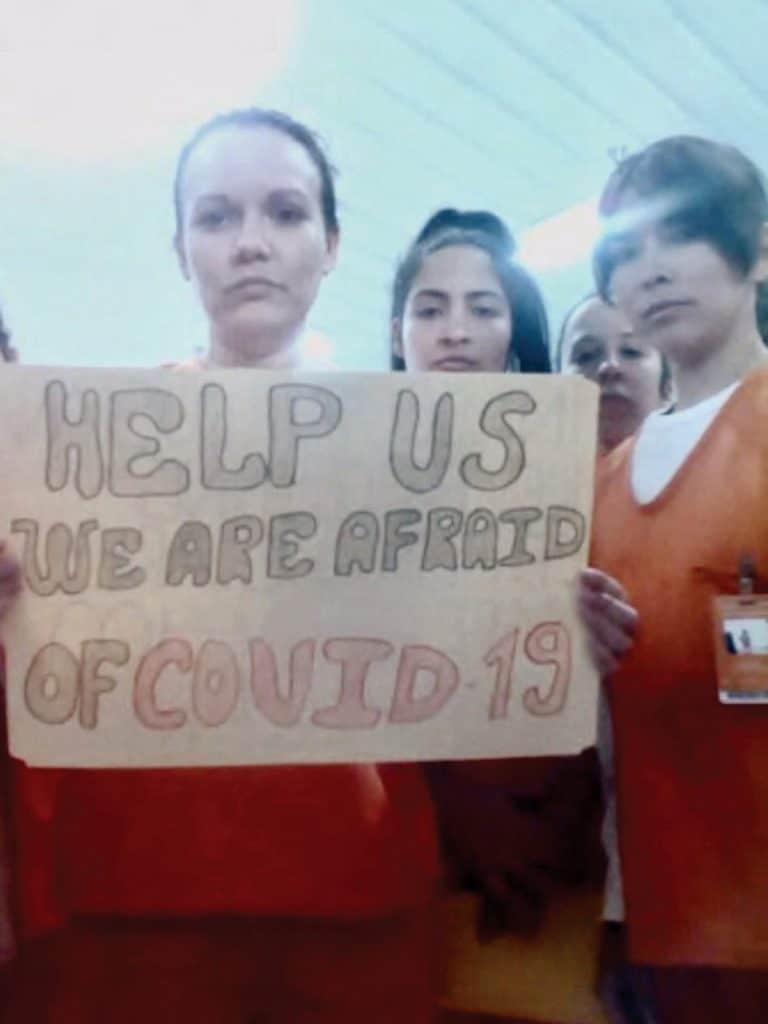

Migrants detained in an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Basile, La., show signs related to the coronavirus disease in early April. (CNS, Handout via Reuters/U.S.)

The women were given hospitality for up to two weeks at El Paso’s Annunciation House, which has set up a COVID-19 protocol. Ruben Garcia, the shelter’s director, told El Paso Matters that they were prepared to take in more ICE detainees if the agency agrees to an orderly release as part of efforts to slow COVID-19 infections.

“We are proud to represent such brave women. They stood up because ICE was not protecting them or the women around them,” said attorney Christopher Benoit. “Release was the only safe outcome for these women. While we remain concerned for those who remain detained, we expect ICE to maintain the improvements in conditions at [the detention center] that were hastily put in place after the lawsuit was filed.”

In an April 22 letter to the local heads of immigration enforcement agencies, six state lawmakers from El Paso urged them to coordinate with local stakeholders “to plan for both the release of nonviolent detainees as well as protocols for the spread of COVID-19 within your facilities.” On April 27, after hearing from several experts, the El Paso Commissioners Court voted 4-1 in favor of a resolution calling on ICE and U.S. Customs and Border Protection to prioritize the immediate release of nonviolent migrants.

“As people of faith, we must do what is right for our sisters and brothers, for our neighbors, and not just protect our own households,” said Cerneka, who has been a Maryknoll lay missioner since 1996. “We must trust in the God that guides us, and we must seek justice for every one of God’s beloved people.”

Maryknoll Lay Missioners published the original version of this article.

Featured image: Heidi Cerneka leaving Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center in El Paso, Texas, in August 2019. (Meinrad Scherer-Emunds/U.S.)

This story was updated for Maryknoll Magazine’s July/August issue.